Hippy Yugoslavia

Azra Nuhefendić, May 26, 2016.

group of young hipsters leave Yugoslavia looking for the Buddhist

monk Čedomil Veljačič, ending up in Morocco

If I say “Bearded”,

most people think of Islamic terrorists. Beards are now a symbol of

everything that is bad: ISIL, Al Qaeda, Boko Haram. It all brings to

mind insurgents and terror.

The West is using armies

and the most advanced technologies, such as drones, to defend itself

against these people. Ancient methods, like building walls, are also

used against beards, and unwanted migrants. Barriers of barbed wire

that have been put up at European borders, to stop refugees from

crossing, have stirred passionate debates “for” and

“against”, as if the method were new. It isn’t.

There has been a triple

barrier of barbed wire for 23 years in Spain, built to stop illegal

immigration from Morocco. The first was put up in 1993, the second in

1995 and the third in 2005. In the Spanish city of Melilla, the metal

barrier is six meters tall, with acoustic and visual sensors and

sharp blades (cuchillas). The blades work well. Each morning the

guards find not only pieces of clothes hanging from the wire, but

also pieces of flesh from those trying to cross the border.

Peace

and Love

My friend Riki believes

that “everything is relative”. He likes these philosophical

axioms, reminiscent of the studies he never finished. Riki has worn a

beard since the first hairs appeared on his face. In his photos as a

teenager he looks just like Jesus: tall, slim, with a soft, kind

expression which shows between a thick beard and long hair.

Forty years ago, when

Riki entered Morocco from Spain, making the journey in the opposite

direction from those of today, the barriers between the two countries

did not exist. He was a typical “flower child”, one of

those bearded hippies with long hair who professed and practiced the

sexual revolution, the free use of drugs, peace, meditation, love,

music, discussing philosophy.

For flower children,

Morocco was then a “must”. They would climb over the boundaries,

overcoming every kind of obstacle to enter.

Although the bearded

hippies were peaceful, they caused a lot of troubles to the Rabat

authorities. Many arrived without any money, and no intention of

working to earn a living.

They camped in the main squares, lay on

the ground anywhere, they dirtied the courtyards of sacred monuments;

they used public transport without buying tickets and they didn’t

have an ID. Also, their philosophy of free sex and their use of drugs

disturbed public order and challenged the rules and customs of the

Moroccan patriarchal society.

Because of their

appearance, they were easily identified.

The police pushed them over

the Moroccan border back into Spain with their bare hands, sometimes

using clubs.

All

sincere wishes come true

But Riki had a saying

also for the black days. He would quote Gandhi: “Every sincere,

genuine wish, sooner or later comes true”. And so, together with

Riki, we got ready to enter Morocco, not at the port of Tangiers,

where the Moroccan police were more severe, but at the smaller Ceuta,

which was less controlled and is an autonomous Spanish city in

Northern African territory.

Our journey started in

the summer of 1974. Originally, we had not planned a stop in Morocco.

Our idea was to go to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka, from the Sanskrit, Lamkä

meaning, “sparkling island”).

India, Sri Lanka, Nepal,

Iran, Afghanistan were also countries which were a “must” to the

hippy community of the sixties and seventies. People would go to do a

pilgrimage, to learn directly from the gurus the postulate of

oriental philosophy, to discuss the sense of life with the Buddhist

monks, how to obtain freedom and how to find happiness.

There was a Buddhist monk

we loved in a special way: Prof. Čedomil

Veljačič. He was one of us, that is, a Yugoslav, from Zagreb.

Veljačič was a university professor. He moved to Sri Lanka, took

the monastic name of Bhikkhu and lived with the poorest monks, the

beggars. However, our Veliačič didn’t stop writing books, articles

and essays. We were enthusiastic about his ideas, we were inspired by

his life, we read his works out loud and discussed them in groups.

For years, we had planned to go and visit him.

But just when we were

about to do so, an unexpected event changed everything.

SOS

Neda, a girl from the

group who lived in Spain with her boyfriend, sent an SOS: he had

disappeared leaving her alone with a small baby, no money and no job.

We therefore decided to change our program; we would first go to

Spain to save Neda, and then decide how to continue our journey.

At the time, Spain was

under Franco, a Fascist dictator, and there were no diplomatic

relations between Yugoslavia and Spain. To enter we needed a transit

visa which was issued at the Spanish embassy in Milan.

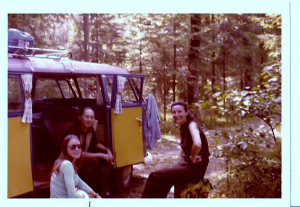

We left at the beginning

of July. In our group we had a future professor of medicine, a

theoretical mathematician who would become internationally

well-known, a philosopher.

All committed hippies with beards and long

hair, extravagant clothes and minimum luggage: only a cloth backpack.

Traveling by hitch-hike

was common at the time among young people, and we didn’t think of

traveling any other way. Everything went smoothly for a while and we

felt that we were part of a well-organized relay.

We travelled in two

groups. The meeting was in front of the “Prado” museum in

Madrid.

We were to meet there in five days time, between midday and

one o’clock, to then go on together towards our friend, Neda.

Her cry for help worried

us so much that we gave up the idea of our much planned trip to the

East. However, when we met her, we found that the situation wasn’t

that serious.

Neda told her story alternating between laughter and

tears.

Algeciras

It’s all for the good, we

decided, discussing if we should return to Yugoslavia or get onto a

cargo ship and head for the East. We favored the idea of going to

Morocco, because it was close and because we now had a baby in our

group. So we headed towards the Spanish port of Algeciras.

The presence of the baby

girl, in a sense, held together our group. We treated her like every

one’s daughter, we looked after her together, we took it in turns to

carry her in a sort of marsupium, a large scarf fixed around the neck

like African mothers do.

With hindsight, I think

we were too relaxed, not to say irresponsible with a baby who was not

even a year old. A new born ran risks on a journey of this kind. But

at the time those problems did not worry us at all.

At Algeciras we had to

stop for three days. The Spanish police would not allow Neda to exit

Spain with a transit visa that had expired three years ago. We had to

wait for a permit from Madrid. The only inconvenience that this

obvious illegality caused, was to force us to stop. Neda was neither

detained nor questioned about where she had been and what she had

been doing in Spain for three years with a transit visa.

From other “flower

children” we learned that it was easier to enter Morocco going

through Ceuta. In Morocco we went slowly

along the Atlantic coast using public transport which cost very

little. We went through Rabat and Casablanca, then left the coast to

visit Marrakech, and finally we arrived at the much desired

Essaouira, the hippy Mecca.

Since we were not common

tourists, we did not stop to look at the ancient city, the monuments,

the impressive medieval fort or the museums, and we did not go

shopping.

We followed in the steps of the famous hippies who had gone

before us: Frank Zappa, Bob Marley and Jimi Hendrix.

We

are from Yugoslavia

We looked for and stayed

in the company of other hippies. At that time, there were so many in

Morocco that we outnumbered the local inhabitants in some small

villages, especially in the small streets and the suqs. The Moroccans

were very kind, they welcomed us, helped us, gave us directions, and

accompanied us to the places we were looking for. But in the twenty

days we were there, nobody asked us to their home. And this, we

thought, was strange. In Yugoslavia it was normal that, after

chatting to someone, you would invite him home.

When we said we came from

Yugoslavia the locals would show enthusiasm, slap us on the back,

give us the name of our president, Tito, and someone would raise two

fingers in a victory sign, or raise their thumb to demonstrate that

all was well. We enjoyed this reaction and didn’t find it strange. We

Yugoslavs were used to being welcomed wherever we went, so the

friendliness of the Moroccans did not surprise us.

We had made no programs,

we had not booked anything in advance, it was all improvised at the

moment. The strongest impression left by that journey was the

slowness with which every thing we did evolved. As if our life was

going at thirty-three instead of forty-five revs.

This slowness could have

been the effect of the grass, which was in abundance. It was offered

to us for free, we shared it with the others as we did with the food.

Lots were smoking, also in our group, even in public, as there were

no restrictions, sitting on the ground in some piazzas or in front of

the bar where the locals joined us in this pleasure.

If you exaggerated, then

the local police would intervene and hit with batons.

After twenty days, we

were on the way back. In Barcelona, five of us climbed into an old

decrepit Volkswagen, given to Neda by a French friend who was going

home. It was a noisy wreck and half broken, and gave the impression

that it would fall to pieces any minute. Inside, it smelt of petrol.

After one thousand kilometers, we also discovered it rained inside.

Is

this car yours?

It was August, in the

peak of the tourist season, and the roads were full of cars, crowds

at the borders. “Our” car had French number plates and

maybe that was why nobody checked us, and we were allowed to pass

unhindered. All went well until we came to the border between Italy

and Yugoslavia, at Fernetti.

That was the last border

before entering our country.

At that time, it was also the border

between the West and the East, the “iron curtain” dividing

the communist world from the capitalist.

That day it was raining

heavily, outside as well as inside the car.

Our baby was restless,

and as soon as we arrived at the border, she started crying.

Two policemen stopped us,

and saluted by bringing their hands to their foreheads.

They thought

we were foreigners, probably judging by our number plate. But as soon

as we showed our red Yugoslav passports, the policeman stiffened, he

studied the inside of the car through the window, he looked at the

bearded passengers and at the baby crying and he looked disgusted.

He asked for the car

papers. We did not have them. Unbelieving, he asked who was the owner

of the car, and Neda gave the name of her French friend. The

policeman did not understand, and then asked if one of us was “him”.

“No”.

“Well, where is he?”

“I think, in

France”, said Neda.

The policeman’s face

turned red.

The conversation

continued amid the baby’s desperate crying, our voices trying to calm

her, and the noise of the rain. The policeman runned his hands

through his hair, and walked a few steps as if to calm himself, then

went towards a colleague.

The two policemen looked

at each other without a word, then one shrugged his shoulders and the

other said: “Go”.

They swore at us, but

they let us go.

SOURCE: Balcanicaucaso