How Klee’s “Angels of History” took flight

Jason Farago, Bbc, 19 Aprile 2016.

|

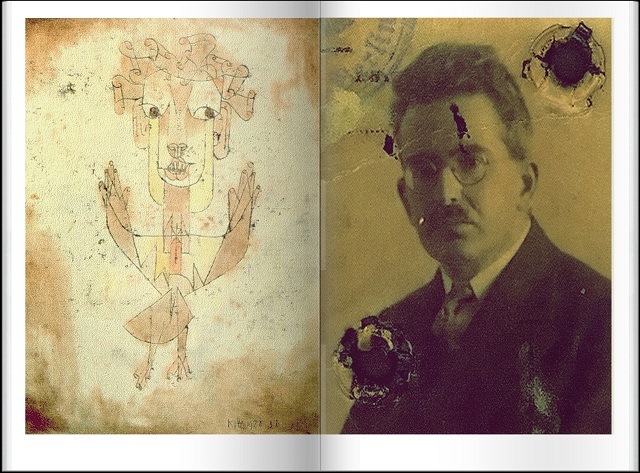

He stands slack-jawed, his four front

teeth protruding from his open mouth like uneven stalactites.

His

head is topped by a mess of curls, which look more like sheets of

parchment than strands of hair, and his jug ears stick so far out

from his cylindrical face that they’re almost flush with his jiggly

eyes.

His dainty chicken feet, joined to spindly legs, are

complemented by large, grand wings – spread open, but tangled and

ungainly. Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, a 1920 oil transfer drawing

with watercolour, is a fearsome but fragile seraph: afloat, aghast,

going who knows where. “This,” wrote Walter Benjamin, the

philosopher who first owned the monoprint, “is how one pictures the

Angel of History.”

The exhibition Paul

Klee: Irony at Work, which has recently opened at the Pompidou

Centre in Paris, features more than 250 paintings and works on paper

by the wily, capricious Swiss modernist.

It comes just two and a half

years after Tate

Modern’s Klee blowout of 2013 – and while you can quibble

with the Pompidou’s decision to mount another retrospective so

soon, the Paris show has one drawing that London didn’t get.

Angelus Novus, barely known during Klee’s life, has become the

artist’s most famous work largely thanks to its extraordinary

provenance, passing through the hands of four important modern

philosophers before entering the collection of the Israel Museum in

Jerusalem.

It’s now in Paris, and its arrival is nothing short of

an event.

Like most critics, I shy away from the

words ‘mythic’ or ‘legendary’ when describing works of art –

in most cases, those words are better left to marketing departments.

But Angelus Novus, perhaps more than any other artwork of the last

century, really has exceeded the boundaries of the gallery: it is an

image more fully understood as a myth than as a work of art.

Wings of desire

Klee was still a young artist when he

created his winding, eccentric angel in the years after World War

One.

He was conscripted into the imperial German forces during the

conflict, but spent much of his service away from the front, which

allowed him to paint and draw throughout WW1. Later, in 1921, he

would join the faculty of the Bauhaus in Weimar and then Dessau.

But

between the end of the war and his acceptance of a teaching job, Klee

secured a small income from a Munich art dealer named Hans Goltz –

who presented a major show of Klee’s work in 1920.

That show, which featured more than

100 works of Klee’s, included for the first time the mystical

monoprint that would absorb a generation of thinkers.

The angel

stands suspended like a dummy or a marionette in a mucky yellow

field; his wings are grand but inadequate, and he seems trapped

between forward and backward motion. That suspension appealed greatly

to Walter Benjamin, who was already making a name for himself as a

heterodox thinker about politics and art.

He bought the artwork in

the spring of 1921 for 1,000 marks – a major sum for a writer who

had endless money troubles – and hung it in his office in Berlin: a

guardian angel, though of a vengeful sort.

Benjamin was not a systematic thinker,

who propounded principles and laws to be tested and affirmed.

He

wrote discursively, dialectically, feeling his way to new ideas

through experiment and contradiction.

In this, he and Klee – an

unconventional modernist, as comfortable with Bauhaus-approved

function as with woozy Surrealism – were one of a kind.

Benjamin

became something like a Klee superfan, and a healthy proportion of

the philosopher’s thinking about art – notably his conception of

“aura,” a numinous quality proper to art that is lost in the

process of mechanical reproduction – can be traced to his

engagement with Klee’s sprightly, dynamic paintings and drawings.

None informed his work more than Angelus Novus, a work he frequently

called his most treasured possession.

But both artist and philosopher had

their careers interrupted by the rise of Nazism: one severely, the

other mortally.

Klee was booted from his teaching job in 1933 and

moved to the Swiss capital, Bern; more than a dozen of his paintings

would end up in the Nazis’ notorious Degenerate Art exhibition of

1937.

As for Benjamin, he had already left Germany just before

Hitler’s accession to power, first for Spain, then for Paris.

His

beloved Angelus Novus was stuck in Berlin, but a friend brought it to

him in 1935: the year of the adoption of the Nuremberg laws, which

redefined German citizenship and left the Jewish philosopher a

stateless man.

When war broke out, Benjamin began writing On

the Concept of History, a fragmentary text – a set of notes,

really – that tried to make sense of the world’s downward spiral.

One image in particular served as his touchstone.

“A Klee painting named Angelus

Novus,” Benjamin wrote in the ninth thesis, “shows an angel

looking as though he is about to move away from something he is

fixedly contemplating.”

(It is in fact not a painting at all:

Klee’s oil transfer technique, a method of his own invention,

involved slathering a piece of tracing paper with printer’s ink,

then placing a drawing paper underneath and scratching the top paper

with a needle to make an impression on the one below.)

Benjamin went

on: “His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain

of events, he sees one catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon

wreckage hurling it before his feet.” Then Benjamin takes a turn

for the clouds: “A storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got

caught in his wings with such violence the angel can no longer close

them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which

his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows

skyward.”

Angelus Novus would have been unknown

to Benjamin’s readers; ever since he bought it from that Munich

gallery, Klee’s work had been out of view.

But the angel, in

Benjamin’s vision, was nothing less than History itself, helplessly

turned the wrong way as it gazes at the wreckage of the past. It’s

a pessimistic, even fatalistic understanding of the state of the

world, one that would have been anathema to leftwing thinkers of just

a decade before. But history had caught up with Benjamin since his

first encounter with the angel in Munich in 1920.

The present was debris-strewn already;

as for the future, who could imagine? Remember that, before the late

1930s, many Jews and left-wing Germans still held out hope that the

Soviet Union could offer a model for a just future once the Third

Reich fell. With the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939, that last hope

was shot.

For Benjamin, the kind of historical progress promised by

Marxist theory – the certainty that class struggle would

necessarily lead to a shining, beautiful future – had been exposed

as a sham. Only the angel remained, to survey the rubble of the past,

and be borne helplessly into the future.

Angel come home

Less than a year later, in a town on

the border between Spain and France, Benjamin swallowed handfuls of

morphine pills: a massive, lethal dose.

The fall of France spelled

disaster for Jewish refugees like him, and Benjamin, who had already

been imprisoned in a transit camp, had no hope left for the future.

But before he left Paris, he confided his papers and his angel to the

author Georges Bataille, who somehow kept them safe in the

Bibliothèque Nationale until the liberation.

After the war,

Benjamin’s possessions were passed onto his fellow Frankfurt School

philosopher Theodor Adorno, another great Jewish pessimist; it then

came to the Kabbalist scholar Gershom Scholem; and finally Scholem’s

widow offered the curly-haired angel to the Israel Museum in 1987.

Having been written about and obsessed over for so long, Klee’s

traumatised seraph at last emerged to the public – in a country

that Benjamin, a complicated Zionist, could only conceive in the

ether.

Klee was not Jewish. But Jewish

mysticism, and the philosophical and historical traditions associated

with the predominantly Jewish Frankfurt School, have become so

intertwined with his youthful masterpiece that Israel seems the

almost inevitable place for the slack-mouthed angel to call home. He

very rarely travels; when the curators of Documenta, the art megashow

held every five years in the German city of Kassel, wanted to include

the work in their 2007 edition, they had to make do with a photocopy.

So the return of Angelus Novus to Paris, the city in which Benjamin

conceived his most trenchant and tragic principles of history, offers

a very rare chance to see the artwork behind the myth, and still to

let the myth propel the artwork forward.

The angel survives amid

catastrophe, powerless but undefeated, assiduously pushing through an

endless and intensifying storm.

“This storm,” Benjamin wrote, “is

what we call progress.”