Does the caste system really not exist in Bengal?

Sarbani Bandyopadhyay, Open Democracy, April 25, 2016

|

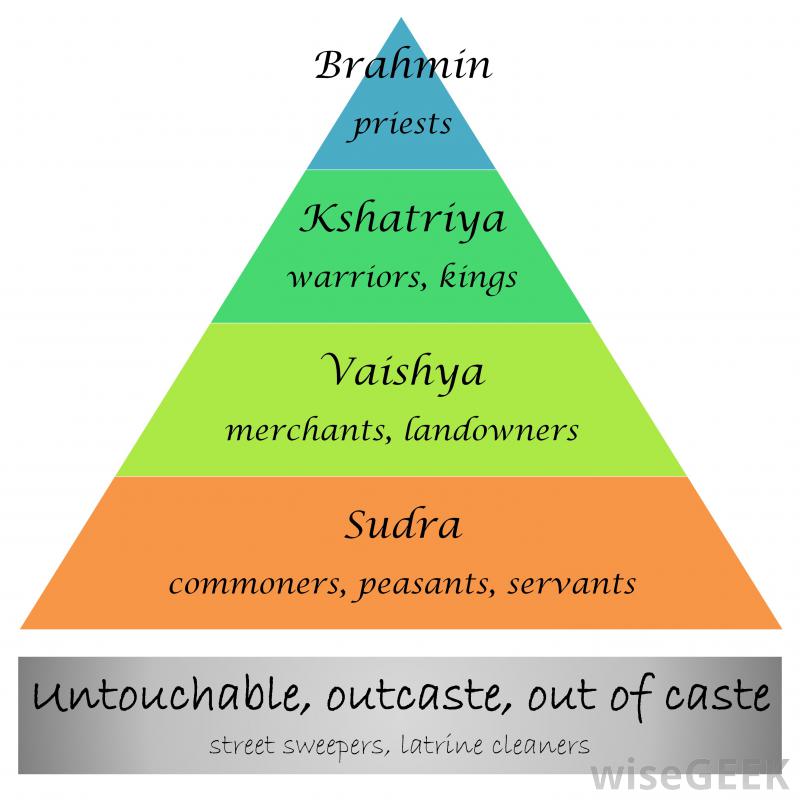

| Indian caste system |

Bengali middle class society is seen

as casteless because caste violence lacks visibility.

One woman’s

story of working as a teacher shows how caste intersects with gender

to reproduce discriminatory practices.

Bengal was the first region of British

India to be colonised and modernised.

The opportunities colonial rule

opened up were taken advantage of by the bhadralok (gentlefolk) who

were mostly upper caste. One of the leaders of the Indian

Independence movement Gokhale

said “what Bengal thinks today India thinks tomorrow” which

captured this avant garde position of Bengal.

In such a vision a

‘backward’ institution like caste was claimed to have no

significant presence.

Consequently, in most academic and popular

domains the castelessness of Bengali (especially) middle class

society became an established fact particularly in comparison with

other Indian states where caste violence and caste-based political

parties have a high visibility.

However, the absence of visible forms

of violence and of caste-based parties does not necessarily indicate

the casteless nature of Bengali society.

The recent ‘suicide’ of

Rohith

Vemula, a Dalit student of Hyderabad Central University, brought

to focus the naked face of caste discrimination in higher education

in many regions of India. However, the pervasiveness of caste is no

less significant in Bengal. The politics of repression has allowed

caste to be insidiously reproduced in both public and private domains

with little resistance.

The story of Lata Biswas, a Scheduled

Caste (SC) person, demonstrates the insidious ways in which caste

prejudice operates in Bengal. Despite evidence to the contrary, Lata

claimed that she did not experience caste in her village where her

caste, the Namasudras, formed the majority of the population. Based

on her narrative I would argue that caste is encountered in Bengal in

mostly middle class spaces such as educational institutions, urban

and non-urban.

Lata passed her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in

Bengali literature with excellent grades, completed her degree for

school teaching and joined a school in 1992.

The school is located in

an interior village of Burdwan district. She was the only Dalit

teacher there and kept overhearing terms like ‘schedule’ in

staffroom conversations between her women colleagues:

Each time I entered the staff room I

would hear this word.

At first I did not understand. Then such

remarks became routine and kept increasing.

Some were like ‘she is

schedule you know, like the maid we have’, someone would reply

‘even my mother’s maid is schedule and now we have a schedule

here again’.

When I did not pay any attention to all these remarks

they started saying new things.

‘Now the last one fled, but this

one seems to be staying, more schedules will come, santhals [an

advisasi group] will come, all those who eat rats, snakes, frogs will

start coming and we’ll have these items for food as well. We should

not drink water from the same jug but now we will have to, oh what

has this world come to’. It was very humiliating because I never

had to face these things when I was a student.

Lata faced other forms of

discrimination which clearly told her that she did not belong.

She

was given a chair and a separate table to sit at apparently because

there was no space for her on the long bench on which teachers

normally sat in the common room.

The next day the cloth on the table

went missing, the newspaper that Lata used in place of the cloth had

a similar fate. Within a couple of days her chair too disappeared.

Finally getting angry Lata squeezed herself on to the common bench.

That forced an open reaction from her high caste colleagues. One of

them instructed her to sit on the floor.

|

| Village market in Burdwan. Credit: Soumyadeep Paul / Flickr |

What led to such animosity toward

Lata?

Middle class/bhadralok society has certain imagery about

non-bhadralok beings, in particular the ‘lowly’ people, popularly

known as chhotolok.

They are seen as uneducated, lacking in culture,

consciousness and agency, as docile and in perpetual need of

bhadralok assistance. The bhadralok self is constructed and asserted

through its other, in this case the marginalised castes. Lata

disrupted this imagery.

She “did not look or behave like an SC”

was another of the remarks that gained ground within a few days of

Lata joining the school. She was assertive and argumentative.

In

disputes with the school administration, she often became the

spokesperson for the teachers.

She hardly lost her temper. Above all

she was a good teacher and students were fond of her.

Lata thus posed

a danger: she was the figure on the threshold that threatened to

disrupt boundaries between the bhadralok and the chhotolok and the

assertion of middle classness by the local bhadralok teachers in the

school.

In an interior village school the need for policing and

reproducing the boundaries of middle classness was felt more by these

teachers who formed a small segment of the local population. Unlike

the earlier incumbent she asserted her ‘rights’, as a woman and

as a Scheduled Caste person, Lata never felt the need to allow (high

caste) men to speak on her behalf or along with her unlike her high

caste women colleagues. Lata was therefore an anomaly: she did not

exhibit ‘feminine’ qualities, or those of her ‘caste’.

She

seemed to have done violence to every understanding of

bhadralok/middle class self in terms of her caste as well as gender.

Lata was tall, not “too

dark-skinned” and was on average “good-looking”.

In short, she

did not have the typical attributes of a scheduled caste person.

These remarks made Lata wonder how the previous incumbent looked.

Through remarks and conversations she gained an understanding that

her predecessor was “quite ugly” and “docile”. She, unlike

Lata, had fitted into both the caste and gender stereotypes that

bhadralok society produced in terms of appearance and disposition.

Since the Durban Conference on Racism

in 2000 there has been much academic debate on seeing caste as a

racial category. Regardless of such debates, in the everyday

perceptions of people caste is seen to have a racial basis. Everyday

life is a fuzzy domain that does not fit into the neat

analytical categories developed by academics.

When Lata claimed that

she “did not fit into the Scheduled Caste category” because her

physical features set her apart from the average figure of the

Scheduled Caste person she was basing her statement on the commonly

held perception that people’s castes could to an extent be marked

out in terms of their physical features.

Besides these, Lata, as mentioned

earlier would rarely get angry. She could argue using what is known

as the language of reason and rationality. In a masculine space

marked by caste (i.e. casted) like the school, upper caste men are

supposed to be logical/reasonable and marginalised castes and women

to be emotional.

Bengali society had been remarkably successful in

not having much meaningful engagement with caste, gender, or even

class. Bhadralok/middle class Left politics has considerably aided

this disengagement. Lata’s narrative shows the process of becoming

middle class and ‘casted’.

Moreover upper caste men went off the

handle in tackling Lata and in preserving the boundaries of spaces

from where Dalits were historically excluded.

Upper casteness and

masculinity that together went into the making of middle classness

suddenly faced a major challenge from Lata, a Dalit woman, who seemed

to trespass into forbidden territory.

Being a ‘meritorious’ student Lata

never needed her caste certificate for admission under the quota

system. At university her “intelligence and grades” shielded her

from forms of prejudice and discrimination.

But in this workspace

despite her grades Lata was taken in not as a General Category

candidate but in the reserved post for Scheduled Castes. What we see

in the workspace is that caste while it cannot be articulated is

nonetheless incessantly articulated in conjunction with that of

gender and local hierarchies. Here the high castes categorised as the

General Category have to pretend that they are ‘uncasted’ whereas

the Scheduled Castes who come in through a different category of

caste do not have access to such privileged forms of

denial/pretension.

They are seen as permanently ‘casted’.

Therefore, Lata was not a person, she was only a caste, marked and

categorised as inferior and inadequate to the rest. Everyday

aggression is the central aspect of this articulation of gendered

caste. Considered as trivial such aggression normalises

institutionalised violence.

These apparently inconsequential forms of

violence considerably affect the sense of self among Dalits aspiring

to be a part of the middle class.