Emmanuel Todd: the French thinker who won’t toe the Charlie Hebdo line

by Angelique Chrisafis, The Guardian, 28.08.2015. A great article about

by Angelique Chrisafis, The Guardian, 28.08.2015. A great article about

Charlie Hebdo, as he is seen by Emmanuel Todd. I would like to publish

this article not to forget the attacks in Paris, and at the same time

not to forget islamophobia and antisemitism in Europe.

After the horror of the Paris

attacks, everyone agreed that the ensuing street rallies were the best of

France. Then a leftwing historian called them a totalitarian sham – and his

critique of ‘zombie Catholicism’ has outraged a nation.

Bleached

by the sun and soaked by the rain, the tattered paper signs still cling to the statue of Marianne, the woman who symbolises all that is beautiful about French liberty, in Paris’s Place de la République. “Never again,” reads one, eight months after two million people amassed here to mark the horror of January’s terrorist attacks – on the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, which had caricatured the prophet Muhammad, and a Paris kosher supermarket – that left 17 people dead.

With

volunteers returning week after week to carefully preserve the posters and relight the candles, the monument to the republic has become an unofficial shrine not just to those who were killed, but to the spirit of the post-attack rally itself. Paris hadn’t seen a gathering of this size since the libération from the Nazis in 1944. The four million people and 50 heads of state who took to the streets across France after the attacks were seen as taking part in a show of national unity and resilience, defending not just liberty, equality, fraternity, but tolerance.

Since

then, the so-called “spirit of 11 January” – the date of the street rallies – has been seized upon by politicians as shorthand for all that is best and still great about France. While the aftermath of the attacks has been bitterly contested, no one questioned the street rallies themselves, which were seen as sacrosanct: the one positive sign in one of France’s grimmest hours.

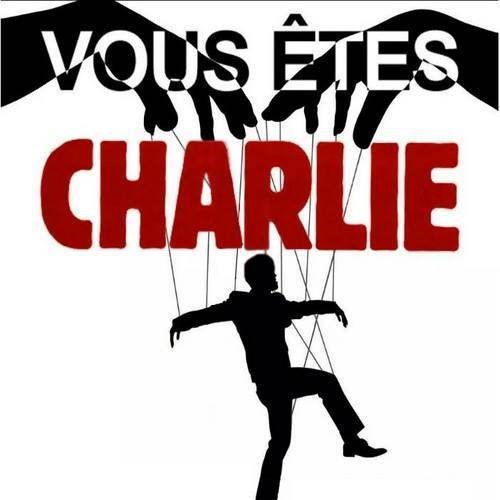

But then a

leading French intellectual, the leftwing historian and sociologist Emmanuel Todd, lobbed what he called his own “magnificently crafted Exocet missile” at the nation, with a book arguing that the street rallies were a giant lie. The rallies, he argued, were not what they claimed to be – an admirable coming-together of people from different ethnic, religious and social backgrounds standing up for tolerance – but an odious display of middle-class domination, prejudice and Islamophobia. To Todd, they represented “a sudden glimpse of totalitarianism”. These “sham” demonstrations, he claimed, were made up of a one-sided elite who wanted to spit on Islam, the religion of a weak minority in France. The working class and the children of immigrants had been notably absent, he said. The most enthusiastic demonstrations, he decided, had occurred in the country’s most historically Catholic and reactionary regions, an affirmation of the middle class’s moral superiority and domination, and their Islamophobic quest for a scapegoat.

Todd’s massively contested and controversial

book, Who is Charlie? – which is published in English next week – instantly became a bestseller and caused one of the biggest intellectual slanging matches of recent years, even by bruising French standards. It was slated as “a polemical ego trip”; Todd was accused on the front page of the daily Libération of“blasphemy against 11 January”. The paper’s editor, Laurent Joffrin, told the Guardian that Todd’s book was not just “absurd, insulting and false” but “gratuitous controversy and harmful”. Todd made every major TV show and magazine cover and was dubbed “the disturbing intellectual”. The Socialist prime minister, Manuel Valls, took the unprecedented step of writing a furious critique of the book in Le Monde accusing Todd of “self-flagellation”. Todd in turn likened Valls’s blind optimism about France to that of Marshal Pétain, the leader of France’s collaborationist Vichy regime in the 1940s.

Who is

Charlie? is now being published across the world with a preface warning that in all western societies “a Charlie lies slumbering” – a horrific event that cleaves society apart and sees the highly educated and well-off stick their heads in the sand.

Sitting in

his flat looking out over the Paris rooftops, wearing frayed jeans and espadrilles, Todd admits he’s now France’s public enemy number one. But he is unrepentant. He says he feels liberated for speaking out. “It’s extraordinary,” he says. “You put out a book that says France had an attack of hysteria on 11 January, and that book immediately sparks an attack of hysteria. It’s a marvellous proof of my thesis. When you produce a reaction like that, it’s because you’ve touched a nerve.”

He pauses.

“It is a bit unpleasant to be insulted every 10 minutes, but I think it’s an astonishing proof of all that’s true in the book.”

“I’m Charlie too”

The

furious row surrounding Todd’s book comes amid a wider soul-searching in France. After a fresh round of terror attacks in France – including a beheading and attempt to blow up a chemical plant near Lyon, and last week’s shooting on a high-speed train from Amsterdam to Paris – the question of what remains of that spirit of 11 January haunts the country. Has France moved on? Or is it still in thrall to the unsettling fears that Charlie Hebdo’s attackers, the Kouachi brothers, ignited, despite the repeated breastbeating of politicians from the far-left to the far-right of the strength of the republican, secular ideal?

As France

came to terms with its national trauma, it was easier for politicians to focus on 11 January as one day of unity than the three fraught days between 7 and 9 January when two brothers who were once wards of the republic in children’s homes massacred some of the country’s best-known cartoonists as well as a Muslim policeman before finally being shot dead by police after a hostage-taking at a printer’s outside Paris. Their target, Charlie Hebdo, had long been under police protection after death threats over its caricatures of the prophet Muhammad. The febrile atmosphere worsened when the brothers’ accomplice, Amedy Coulibaly, also French born and bred, touched the rawest of nerves by killing four people in a siege of a Paris kosher grocery store days after shooting dead a policewoman while reportedly on his way to attack a Jewish school.

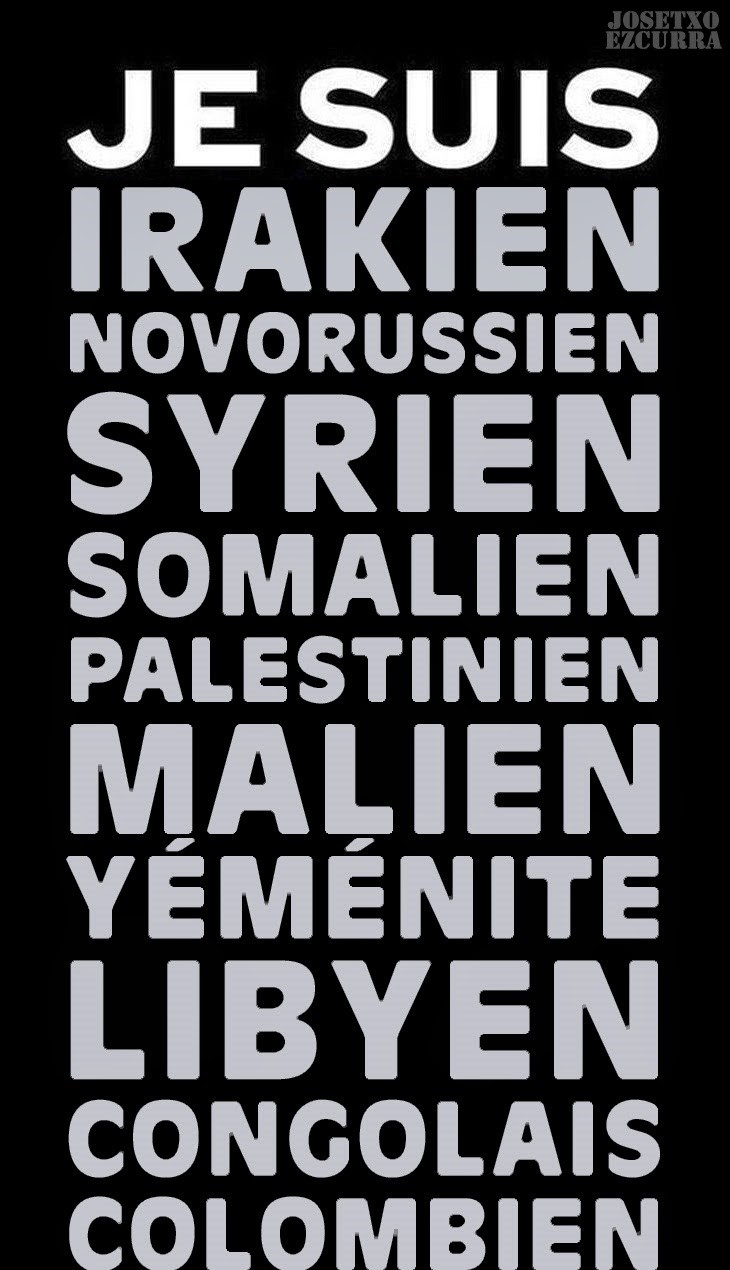

The slogan

“Je Suis Charlie” (I am Charlie) became a worldwide rallying cry but proved complex, and to some extent, excluding. It didn’t fit with those who utterly condemned the shooting, but didn’t agree with the magazine’s caricatures of Muhammad. Scores of disrupted minute’s silences in schools, particularly in the restive banlieues, or suburbs, appeared to highlight the uneasy relationship between teenagers, often from immigrant minorities, and their teachers. Amid this, the French government cracked down on speech “deemed to glorify terrorism”. A series of cases rushed through the courts resulted in heavy prison sentences, some handed down to people who were drunk. One man with slight learning difficulties was sentenced to six months in prison for drunkenly shouting at police officers in the street: “They killed Charlie, I laughed.” Rights groups protested. The debate intensified after it emerged that an eight-year-old boy was questioned by police for saying at school “I am with the terrorists,” later admitting he didn’t know who the terrorists were or even what terrorism meant.

Valls

warned of “territorial, social and ethnic apartheid” in France and launched a plan for greater mixing in social housing and measures against discrimination. This hint that homegrown terror may have a homegrown cause sparked a chorus of disapproval from politicians. Then came the government’s new increased surveillance laws, which caused a storm over civil liberties.

All the

while, people were looking for answers. Non-fiction book sales rose markedly as readers searched for explanations of the terrorist attacks. Voltaire’s Treatise on Tolerance, first published in 1763 – the source of the ideas that were paraphrased as “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it” – was reissued, and sold more than 90,000 copies in four months. Scores of books were published about the “Spirit of 11 January”, debating everything from the right to blasphemy, introduced by the French revolution in 1789, to the place of Islam in France.

It was

against that background that Todd launched his Exocet.

He hadn’t

gone on the 11 January rallies himself, although he knew the economist Bernard Maris, who was killed in the Charlie Hebdo attack. But he said that when he opened the newspaper the next day and saw the maps of where rallies had taken place, he saw a pattern that infuriated him. “Here was clear fraud. The street demonstrations were the self-glorification of the French middle class. That made me explode.” He saw it as France refusing to look at the economic stagnation and deep inequality that might have led to the horror of the attacks.

He wasn’t

previously a “French-basher” but now calls himself “a Frenchman exasperated by his own society”. He wrote the book in 30 days, getting up at 3am, but is at pains to say it was based on 40 years’ previous research.

Todd’s

central argument is that there are fundamentally two Frances. There is a “central” France, including Paris and Marseille and the Mediterranean, where there is equality on the family level and a deep-rooted attachment to secular values of the French revolution and the republic. Then there is a France of the periphery, for example, the west or cities such as Lyon, which has stayed true to the old Catholic bedrock, where people may no longer be practising Catholics, but they’re still infused with all the social conservatism of that Catholicism, its hierarchies and inequality. He calls this “zombie Catholicism”. Infuriating his critics, Todd maintains that the post-attack rallies represented zombie Catholicism on the march.

Despite

the row, he stands by the idea. “France is always double,” he says. “That’s why you never know if it will collapse or get back on its feet.”

Todd, who

comes from a cosmopolitan family of writers and is distantly related to the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, came to fame for predicting the fall of the Soviet Union in 1976 and more recently for suggesting the US is an empire in decline. He has long argued that family structures explain why people adhere to certain ideologies, and has pleaded for France to leave the euro.

He claims

in Who is Charlie? that France is no longer a place of liberty, equality, fraternity, but instead is a kind of pseudo republic favouring only the middle class while the working class and children of immigrants have been excluded. He feels France has much that is “marvellous”, including its welfare and social security safety net. “But it has stayed marvellous only for the top half of society.”

However,

Todd’s argument that you can tell a lot about the “unconscious” drive of the people on the street rallies just from the political and religious traditions of where they come from has been widely challenged. He says he’s not suggesting everyone on the march was a rampant middle-class Islamophobe, but that the overall effect of the mass rally was just that. “After the rallies, we saw Islamophobic behaviour everywhere; it loosened people’s tongues.”

Todd says

he was most hurt by attacks on his methods and stands by what he says is “serious statistical analysis”.

One of his

key concerns is “the wave of Islamophobia” in France, which he says is echoed across the west.

Dismissing

Charlie Hebdo as a “bad magazine”, he said France’s new obsession with the right to blaspheme is a pointless over-reaction. To him, blasphemy is now hailed not just as a right but a kind of duty. He feels that freedom of expression is clearly not under threat in France, so it’s wrong to focus mainly on that in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attacks. He said he felt very uncomfortable watching the French Muslim comedy star Jamel Debbouze on TV talking about his mixed marriage and joys of living together, being pushed to say he agreed with caricatures of the prophet, as if that was the only true measure of how French he was.

“Yes, of

course, there’s a right to blaspheme,” Todd says. “But one must also have the right to say that blasphemy is not a priority and that it’s idiotic. With my book, I was demanding the right to counter-blaspheme: to say that the caricatures of Muhammad were obscene, rubbish, totally historically out of sync and the expression of rampant Islamophobia. And, for saying that, I was accused of complicity with the terrorists.” He felt vindicated by the reaction. “It was fascinating to see people demonstrating for the right to freedom of expression and then trying to shut others up.”

The

maternal side of Todd’s family is Jewish. “This is probably the first time in my life that I’ve written a book as a Jew,” he said. When a young gunman Mohamed Merah opened fire outside a Jewish school in Toulouse in 2012, killing four, Todd put the antisemitic element to the back of his mind; likewise when a French gunman killed four at the Jewish museum in Brussels last year. But with the attack on the kosher grocery store, which he feels has been overshadowed by the Charlie Hebdo killings, he said antisemitism was clearly at crisis point. His theory is that the rise in Islamophobia is in turn stoking antisemitism in run-down suburbs, and that antisemitism is growing in the middle class.

He feels that

“France is a sick society”. He says its economy is faltering, unemployment is sky-high, inequality is the norm and yet, rather than properly get to grips with that, the country went sleepwalking into the January rallies like sheep.

He says,

as a historian, it’s not his place to find answers for the future, but feels that they rest on accommodating Islam into French life. He warns that, as politicians focus on their ageing electorate, “there’s a phenomenon of reducing to silence a large part of the young population, something you’ve become conscious of in the UK long before we have”.

He says

France is perceived abroad as being a country that is asleep. “Most other countries, including the UK, are trying to adapt. I won’t say that David Cameron’s politics, which are destroying the UK, are a good way to adapt. But in the UK, there’s an idea that at least things need to adapt. In France, we have a ridiculous political system in which everyone talks about reform but does nothing. And that inaction produces a phenomenon of exclusion, destroying the lower half of French society.”

He sighs.

“There’s a part of French society that’s rotten, and nothing is being done.” |

– See more

at:

http://www.tlaxcala-int.org/article.asp?reference=16033#sthash.mQ8bkB2p.dpuf

at:

http://www.tlaxcala-int.org/article.asp?reference=16033#sthash.mQ8bkB2p.dpuf